After 28-year-old Ralph Bowen married his wife Zula in Denver in 1894, he had decisions to make—where he and Zula would live, and how he would earn a living. He had heard about the Cripple Creek mining district and decided this place offered him a fresh start and a chance to build his life the way he wanted.

Bob Womack discovered gold there a few years earlier, in 1890. A gold rush followed Womack’s strike, and overnight a camp appeared in the goldfields. It was a beehive of activity: prospectors searched the hills, miners swung picks and blasted rocks, carpenters built houses, merchants opened stores, bartenders poured drinks, and gamblers played cards under a canopy of cigar smoke.

The real gamblers, though, were the ones who placed their bets on opening a business. Bowen, a two-fisted, bigger-than-life entrepreneur, with ambition as big as Pikes Peak, took that gamble, and started a sawmill near the town of Gillett in the mining district.

It was a good business, as the demand for lumber was high in the growing mining district, and he was determined to succeed. As his saws buzzed and the sawdust flew, the sawmill reduced rough pine logs into planks, studs, and shingles. Horses plodded down dusty roads, pulling wagons—one after another—of Bowen’s lumber to town.

Shortly after Bowen established his sawmill, the sharp, cold winters of Cripple Creek signaled more possibilities, and he set up another enterprise, the Bowen Ice Works. A recently discovered early twentieth-century archive of rare photos, at the Cripple Creek District Museum, freezes time and documents Bowen’s ice business in the gold camp. And now, through these historic photos, his story can be told.

Business was the major theme of Bowen’s life story in Cripple Creek. His ice operations were far removed from Cripple Creek’s Bennet Avenue—the city’s broad street of business and enterprise. He knew he would not make bags of money but simply have a good life in this beautiful part of Colorado.

Bowen quickly became a skilled iceman: Each winter he harvested a large natural ice crop from his spring-fed pond near Mount Pisgah. Harvesting ice from his pond, where nature and technology merged into one, was a winter routine—once the ice grew to a thickness of a foot or more. To check the thickness of the ice, workers drilled holes into it with augers, and then reached down and put a ruler into the hole (Jones, 1984). The resulting measurements let them know if the ice was thick enough to start the harvest.

Once the ice reached a foot thick, workers shoveled snow off the pond’s surface and piled it into deep, white windrows. Next, the workers “scored” the surface of the ice with grooves in a checkerboard pattern, using horse-drawn plows. The straight-line grooves showed the workers where to cut the ice (Pepe, 2017). Using a long saw, the workers cut the ice, and the sounds of sawing ricocheted around the pond like a cue ball (Cummings, 1949). This work chilled the ice crew to the bone. The cold brought a fresh scent to the mountain air. Nearby, Steller’s jays perched in the green shadows of pine trees and watched Bowen’s men remove ice blocks while mule deer ruled the forest.

Once the workers cut the ice, they used long poles, called pikes, to move the floating ice blocks toward the shore. Then they guided blocks of ice, pulled by horses, up inclined ramps to the top of the icehouse. Men stacked the ice like firewood and packed it as tight as a box of pencils. Sawdust from Bowen’s sawmill separated the layers of ice from each other and served as insulation to prevent melting. The storage building preserved the ice for delivery to residential and commercial customers.

Each spring, as weather turned warmer, the delivery of ice began to hotels, restaurants, storekeepers, and housekeepers in Cripple Creek. As his ice trade grew, so did his profits. Bowen, along with his horse and wagon, became a part of the Cripple Creek summer street scene. At a time before electric refrigerators, he made daily rounds in his horse-drawn wagon, delivering ice for wooden iceboxes. These insulated wooden iceboxes had shelves inside for food.

Customers placed a card in their window to let Bowen know how much ice they wanted. Based on the card, he then pulled ice out of his wagon using tongs. He lifted the block of ice onto a thick sheepskin pad on his shoulder and carried it to the house, placing it inside the icebox (Jones, 1984). If the block of ice did not easily fit into the icebox, Bowen used an ice pick to trim it. He carried a small scale in his pocket to assure customers they received the correct amount of ice. After deliveries, he mended harnesses and fixed his tools.

|

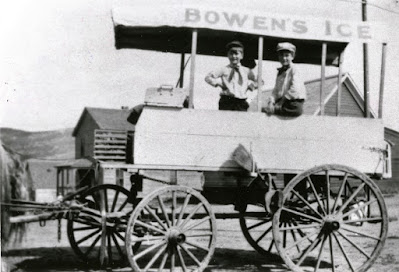

| Figure 6. Ralph Bowen and his ice wagon pulled by two white horses. Unknown photographer. Undated photo. Ralph Bowen photograph collection, courtesy of the Cripple Creek District Museum, CCDM 8704A. |

Bowen and his family lived in a large, rambling frame home on a grassy rise at the base of Mount Pisgah, near his pond. A fireplace kept his place warm on wintry days. Parted drapes let the sun in through the windows. Here he washed up with hot water to ease his aches and dog-tiredness. In the quiet comfort of the evenings, he likely relaxed in his special chair and picked up the Cripple Creek Morning Times to read.

Bowen was committed to his four children. He had two daughters: Dorothy and Elizabeth; and two boys: Ralph Jr. ("Bud") and Palmer ("Little Chap"). With a smile on his face, he drove his ice wagon while Ralph Jr. and Palmer hitched rides in the back. In the winter, groups of children bounced along in Bowen’s large wooden sled pulled by two white horses.

The seasons set Bowen’s life in Cripple Creek in a patchwork of days: harvest ice in the winter, sell it in the spring and summer, and work the sawmill in the fall. Few lives in the gold camp were more toilsome.

It cannot be denied Bowen risked everything by operating two businesses in the district, but he thrived. He forged an independent life, and for over three decades he delivered ice to Cripple Creek and ran the sawmill. He provided day wages to six or more workers. He never failed in any important undertaking, and by sheer effort overcame all difficulties that stood in his way. He had a proprietary pride beyond words.

So, too, he was at ease with being a family man while selling ice and lumber. He took his family boating on his pond and entertained local children with rides and made a few moments of their lives richer.

Ralph Bowen’s photograph collection documents an important part of a life in the mining district. And these photographs keep Bowen from slipping into obscurity as he drives his ice wagon through time without end.

Note: Ralph Bowen later left the Cripple Creek mining district and homesteaded in Eden Valley, Wyoming. Ralph Jr. became a music teacher in Springfield, Illinois. Palmer ranched near Cañon City, Colorado. Dorothy married a newspaper man and lived in Fort Collings, Colorado. Elizabeth was a librarian in Craig, Colorado (Dunn, personal interview).

Acknowledgments

I thank Shelly Veatch and the Colorado Springs Oyster Club critique group for reviewing the manuscript, and Dr. Bob Carnein for his valuable comments and important help in improving this paper.

|

| . Workers shovel off yesterday’s snow while others saw ice on a pond during the long, dark winters. From the S. W. Veatch stamp collection. |

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.