By Steven Wade Veatch

A long-forgotten Colorado Springs rockhounding memory reawakened for me as I looked at a vintage postcard (figure 1) that shows the crossroads of High Drive and the Colorado Springs and Cripple Creek District Railroad, also known as the Short Line Railroad. It was just a short distance from here that I had stepped away from my motorcycle to take a deeper look at the area. On the edge of a steep slope, the shape of some crystals leaped to eye and mind.

|

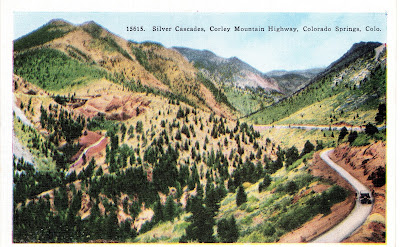

| Figure 1. Intersection of High Drive and the Short Line railroad. Note buggy tracks on High Drive. Postcard from the collection of S. W. Veatch. |

I thought about the rich history of the area. Workers completed the Short Line in 1901. Today, the Gold Camp Road follows the old route of the railroad as it winds its way up the mountain to the goldfields of Cripple Creek. Both the Short Line and High Drive were used to access the Bruin Inn (figure 2), which was located near Helen Hunt Falls.

General William Jackson Palmer, founder of Colorado Springs, commissioned the construction of the High Drive in 1903 as a scenic carriage route. Gold Camp Road follows the old Short Line Railroad between Colorado Springs and Cripple Creek. The railroad went bankrupt in 1919. W. D. Corley purchased the line in 1922, removed the rails, and converted the right-of-way to a toll road (known as the Corley Mountain Highway) for cars in 1926.

|

| Figure 3. The red arrow on the topographic map shows the intersection shown in figure 1. The post card photo was taken a short distance north of Helen Hunt Falls and the Bruin Inn. |

In March 1982, I was riding my Yamaha all-terrain motorcycle with a rock-hunting friend, Jerry Odom, who was also on a motorcycle. I was working for 7-Eleven then, and had the day off. Jerry was an officer with the Colorado Springs Police Department. We rode past the intersection of High Drive and the Gold Camp Road, continued on the Gold Camp Road, and entered North Cheyenne Cañon, a 1,000-feet-deep cut into the billion-year-old granite. With its hidden geological wonders, the area has long been a treasure trove for gem and mineral hunters. We did not make it far, as the road was soon filled with snow and we had to stop. We turned our motorcycles around and then stepped off of them to stretch our legs.

|

| Figure 4. View of the Corley Mountain Highway, now known as the Gold Camp Road, on the southwest side of Colorado Springs. Postcard from the S. W. Veatch collection. |

We lost the sun as it sank below the canyon rim. Shadows lengthened as the afternoon moved on, and the air was cold. Some snowflakes under a pine tree swirled about on a lofting breeze. Below, a stream flowed over immensities of time and through cycles of erosion and deposition.

I looked at the ground and saw, next to the road, near the edge of the canyon, a hunk of Pikes Peak granite that had been broken loose by a road grader. I noticed that it had a long cavity running through it. I looked a little closer and found crystals that resembled two tiny Egyptian pyramids that had been glued together. I had stumbled on a pocket of zircon crystals!

The discovery of the zircon crystals’ unique shapes among the granite rocks was exciting—a moment of wonder that linked me to Earth’s ancient past. These reddish-brown crystals held a billion years of history, adding deep time to my early spring adventure. The excitement continued beyond the discovery as we rode back down the mountain and then into Colorado Springs.

Collectors continue to find zircons at a half-dozen sites in the area. At the nearby Eureka mine— where prospecting is more intentional—collectors use a black light in the dark tunnel that causes zircons to fluoresce a vibrant yellow, making them easy to find.

|

| Figure 5. Zircon crystals. From the L. Canini collection |

|

| Figure 6. Zircon crystals. From the L. Canini collection |

|

| Figure 7. Zircon crystals under a black light. From the L. Canini collection. |

|

| Figure 8. Zircon specimen from the North Cheyenne Cañon, El Paso County, Colorado. Courtesy of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. DMNS EGM.10328. |

This is an experience that I vividly remember nearly 44 years later. It is just one of many adventures for me hunting for rocks, minerals, and fossils in the Pikes Peak region. For both expert geologists and amateur rock collectors, finding a zircon crystal sparks a passion for rockhounding and searching for local mineral treasures that are part of El Paso County’s rich geological heritage.

Acknowledgments:

The author thanks Eric Swab for his assistance with this manuscript. Bob Carnein improved this manuscript. Many thanks to his years and years of editing my work.

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.