By Steven Wade Veatch

Balanced Rock, in Colorado Springs’ Garden of the Gods Park, is an example of a type of geologic feature called “precariously balanced rocks,” or PBRs. These interesting rocks are common in the American West, where dry climates preserve them. They are also found worldwide in other climates.

PBRs can vary in size from small boulders to massive stone monoliths weighing thousands of pounds—and many are precariously perched on a pedestal. They look like they could topple over in a strong wind.

People have long been fascinated by PBRs. In the past, certain cultures linked these rocks to spiritual or supernatural realms and used them in religious rituals. Balanced rocks also held spiritual significance in Native American culture as markers for guiding mystical journeys. They were also used by early Anglo settlers as they made their way to new homes in the west. In addition to their spiritual significance, PBRs have become popular tourist attractions, and in many cases are surrounded by parks where tourists come to see these incredible geological wonders and marvel at their implausible balancing acts.

|

| Figure 3. Big Balanced Rock Near Douglas, Arizona. Postcard circa 1948. From the collection of S. W. Veatch. |

|

| Figure 4. Balance Rock, Idaho. Postcard circa 1940s. From the collection of S. W. Veatch. |

|

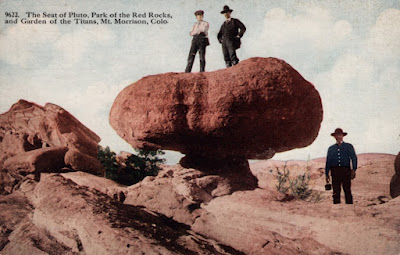

| Figure 5. An old postcard view of the mushroom-shaped “Seat of Pluto” rock formation in the Red Rocks Park, Morrison, Colorado. Postcard circa 1912. From the collection of S. W. Veatch. |

PBRs are formed in several ways. Some PBRs result from weathering and erosion. When water percolates through fractures in rock, those fractures can grow and ultimately break the larger rocks into several smaller pieces. Over thousands of years, as erosion lowers the ground level, the rocks are exposed at the surface, and are frequently stacked on top of one another. Weathering and erosion of the exposed rock by wind, rain, and relentless cycles of freezing and thawing removes rock material around the balanced rock, leaving the harder rock behind. Over time, a rock pedestal is formed as the softer material erodes away, leaving only a small base of support protected by the more resistant rock.

|

| Figure 7. A sandstone PBR at Garden of the Gods, Colorado Springs, Colorado. Photo date 2020 by L. Canini. |

|

| Figure 8. A sandstone PBR at Red Rocks Open Space, Colorado Springs, Colorado. Photo date 2020 by L. Canini. |

|

| Figure 9. A sandstone PBR at Garden of the Gods, Colorado Springs, Colorado. Photo date 2020 by L. Canini. |

|

| Figure 10. A sandstone PBR at Palmer Park, Colorado Springs, Colorado. Photo date 2020 by L. Canini. |

A glacier can create a PBR when it snatches up a boulder and carries it away in the moving ice. When the glacier melts, it drops the entrained boulder onto its new location (see fig. 2, 6, and 15). Glacial meltwater then removes the softer till and outwash, leaving larger rocks (erratics) perched on smaller rocks. Gravity is another way of creating a PBR when it pulls a larger rock down a slope that comes to rest precariously on another rock or rocks (figure 11).

|

| Figure 11. A PBR in Mount Manitou Park, Colorado. A large boulder of Pikes Peak Granite has moved downhill and rests on a smaller boulder. Postcard circa 1912 from the collection of S. W. Veatch. |

|

| Figure 12. A granite PBR. Devils Head area, part of the Rampart Range of the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. Photo date 2020 by L. Canini. |

|

| Figure 13. A PBR perched on granite at the Lake George Community Park, Lake George, Colorado. Photo date 2020 by L. Canini. |

PBRs are not only fascinating sights, but by remaining balanced, reveal a lack of regional seismic activity from the past (Rood, et al., 2020). These balanced rocks also indicate the maximum intensity of past earthquakes (Brune, 1996; Imbler, 2020). By collecting data on PBRs, seismologists examine uniquely valuable data on the rates of rare, large-magnitude earthquakes.

Over time, erosion, weight changes, or earthquakes will cause PBRs to topple. Tragically, acts of vandalism can destroy PBRs, as seen in 2012 when a scout leader and a friend pushed over a small PBR in Goblin Valley State Park in Utah (Botelho and Watkins, 2014).

|

| Figure 16. A PBR stands as a lonely sentinel in Arches National Park, Utah. Photo date 2013 by S. W. Veatch. |

PBRs show the power of nature and add to the incredible beauty that is found in the natural world. These rocks are a reminder that the forces of nature can transform even the most stable objects. Whether seen as cultural artifacts, geological curiosities, or sources of seismic information, precariously balanced rocks never fail to fascinate and inspire awe.

Acknowledgments

The author greatly appreciates the help of Laura Canini of the Colorado Springs Mineralogical Society, who provided interesting discussions and photos of Colorado PBRs.

References and Further Reading

Botelho, G. and Watkins,T., 2014, Ex-Boy Scout leaders involved in pushing over ancient Utah boulder charged. Retrieved from CNN https://www.cnn.com/2014/01/31/us/utah-boulder-boy-scouts/index.html on January 29, 2023.

Brune, J. N. 1996, Precariously balanced rocks and ground-motion maps for Southern California. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 86 (1A): 43–54.

Imbler, S, 2020, Why Scientists Fall for Precariously Balanced Rocks, Atlas Obscura, January 9, 2020, Retrieved from https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/precariously-balanced-rocks?fbclid=IwAR2DS3LCMGd0xYlw9OXG3lgCDeLtgWNgpTA2Er7tnNzEompibGCbnXNlHN0 on October 1, 2022.

Rood, A.H., Rood, D.H., Stirling, M.W., Madugo, C.M., Abrahamson, N.A., Wilcken, K.M., Gonzalez, T., Kottke, A., Whittaker, A.C., Page, W.D. and Stafford, P.J., 2020, Earthquake Hazard Uncertainties Improved Using Precariously Balanced Rocks. American Geophysical Union Advances, 1: e2020AV000182. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1029/2020AV000182 on 10/01/2022.

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.