Francis “Frank” Finegan (1835-1914) was an adventurer who fought in the Civil War. And he was among the first group to arrive at the goldfields of the Cripple Creek mining district, where he located and patented several mines. Stockholders elected him president, treasurer, and general manager of the Requa Savage when he incorporated the mine on April 26, 1894 (Colorado State Mining Directory, 1898).

Finegan left enough of a record to trace his interesting journeys and see the stormy corners of his life. He was born in 1835 in Loughrea, County Galway, Ireland. In 1854, he sailed out of Liverpool to New York City (Portrait and Biographical Record of the State of Colorado, 1899). He then left New York City and lived for a time in Hartford, Connecticut, where he worked as a stonecutter and mason. He moved to California in 1857 and mined on the American River, the site of the original 1848 gold discovery in California. One year later, he sailed to Australia and farmed near Ballarat. With three partners, he located a gold mine near there. The partners worked it until 1859, when they sold their interests, each pocketing $35,000—a whopping $1,091,375 in 2020 dollars (Portrait and Biographical Record of the State of Colorado, 1899).

Finegan left Australia and returned to California for a few months in 1860. He then moved to New York City. On April 12, 1861, at 4:30 am, while Finegan was fast asleep, Confederate General Beauregard ordered his gunners to open fire on Fort Sumter, South Carolina. Cannons roared like a crack of thunder. Explosions lit up the darkness and smoke settled over the fort. Thirty-four hours later, the besieged Union garrison raised a white flag and surrendered. The Confederates committed an act of war that forced President Abraham Lincoln to act. Two days later, Lincoln called for volunteers to fight in a war to preserve the Union.

Finegan answered Lincoln’s call. He joined the 69th New York Regiment that month and was mustered into service for three months. The 69th Regiment was part of the Irish Brigade, which at the beginning included the 63rd, 69th, and the 88th New York Regiments and the 28th Massachusetts Regiment. The 116th Pennsylvania Regiment, made up of Irishmen from Philadelphia, was added during the fall of 1862 (R. Sauers, personal communication). The Irish Brigade quickly built a reputation for fierce fighting on the battlefield, and Finegan found a passage into hell when he fought in many of its engagements.

The 69th New York Regiment fought in the First Battle of Bull Run under the command of General William T. Sherman. During that battle, Confederate forces took Finegan prisoner. The Confederates released him on parole (Both sides had no means to take care of prisoners; Grant later stopped the practice of releasing prisoners). Once released, Finegan reenlisted for three years and returned to the battlefield.

Finegan saw combat at the Battle of Fair Oaks (Henrico County, Virginia) on May 31 and June 1, 1862. It was there that he saw the use of Union balloons, some reaching altitudes of over 1,000 feet, to report enemy positions and direct artillery fire.

Later, at the Cornfield Battle of Antietam (September 17, 1862), Finegan went down hard with a savage head wound while carrying the flag (Portrait and Biographical Record of the State of Colorado, 1899). Almost 8,000 Union and Confederate soldiers were killed or wounded in the Cornfield Battle.

Finegan fought in the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1 - 3, 1863), where he witnessed horrific sights. He surely would have heard flags flap in the wind and bullets whizz by. The air was heavy with the scent of blood. There were fields of slaughtered and decaying bodies everywhere. While marching down a road jammed with troops and shining bayonets, he doubtless heard the cries of the wounded and the amputees, and then noticed a heap of amputated legs, feet, arms, and hands under a tree. During the Civil War, doctors performed a lot of amputations to prevent wounds from becoming infected. Antibiotics used to kill germs had not been invented yet. Gettysburg was the bloodiest clash of the Civil War and came with a high casualty list for both sides: 7,058 died; 33,264 wounded, and 10,790 went missing (LeBoutillier, 2017). As the war continued to intrude into his life, Finegan was becoming a hardened fighter who learned his skill on the battlefield.

Finegan, who was likely detached from the 69th Regiment, took part in the siege of Vicksburg (May 18 – July 4, 1863) as Grant directed artillery fire at the city. The air burst into flames as the shelling continued, and then Grant’s army relentlessly attacked the city for over 40 days. Eventually, the food and supplies ran out, forcing the soldiers and citizens of Vicksburg to eat mules and rats (Stanchak, 2011). The Confederate forces at Vicksburg surrendered on July 4, 1863. Amid the broken bricks and fires, a few homebound citizens must have watched through shattered windows as the Union forces marched by.

Finally, Finegan survived two later battles: the Battle of the Wilderness (May 5 - 7, 1864), in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, and the Spotsylvania Court House Battle (May 8 - 21, 1864).

Finnegan was among many who witnessed the great suffering, horror, madness, and destruction of the Civil War that resulted in a horrific cost of life in the nation’s bloodiest war—at least 750,000 soldiers died, hundreds of thousands of others were wounded in battle, and an unknown number of civilians perished (McPherson, 2015). An estimated two percent of the population was killed (Ward, 1990). The Civil War set four million slaves free, brought the downfall of the Southern planter aristocracy, and preserved the Union as one nation, indivisible.

|

| Figure 2. Battle of Gettysburg. Painting by Thure de Thulstrup. Original scan: Library of Congress. Public Domain. |

Having miraculously survived these bloodbaths, Finegan returned to New York City, where he mustered out in June, 1865. After he left the Army, Finegan returned to Australia once again. He settled in Victoria, where he worked in contracting and building. Then, in 1874, he moved to San Francisco where he worked as a stonecutter and mason. In 1880, he moved once again, this time to Colorado Springs, Colorado. He started a building business and lived at 225 S. Cascade. In 1881, he was elected alderman and served six years on the city council of Colorado Springs (Portrait and Biographical Record of the State of Colorado, 1899).

In the shadow of Pikes Peak, peripatetic Finegan was becoming restless; excitement was absent in his life. This was about to change in 1891, when gold fever from the Cripple Creek mining district infected Finegan. The only cure for him was to come to the district and step into mining. About the time Finegan arrived in the district, a prospector, with the swing of his pick, revealed a streak of bright gold ore at a spot on the side of Beacon Hill. This discovery set in motion the establishment of the Requa Savage mine, in which Finegan was the driving force. Finegan incorporated the Requa Savage so optimists could invest in the mine. Now there were funds to hire engineers and miners and to buy machinery to develop it.

Some maintain that Finegan named the mine after “Uncle” Benjamin Requa, an early settler, or for the nearby Requa Gulch. The gold mine was near Arequa, one of the oldest towns in the district. By 1896, the town of Arequa, named after Ben Requa, included the “A” as the first letter of its name, as seen in the map in figure 3 (Mackell-Collins, 2014). The Requa Savage was on the north side of the Gold Dollar mine (see map figure 3).

|

| Figure 4. View of Beacon Hill. A red arrow shows the location of Arequa. Photographer unknown, date mid-1890s. From the Olla Burris collection, Cripple Creek District Museum. |

As time passed, the Requa Savage became known as a modest producer. According to the Mining and Engineering Journal (1910), the Requa Savage mine, in 1910, shipped two carloads of ore assaying at one ounce per ton. Other carloads yielded less gold, but the mine produced $100,000 that same year.

The passage of time would not be kind to Frank Finegan. He fought cancer but lost that battle and died on October 22, 1914, in Colorado Springs, at 79. His family buried him in the Evergreen Cemetery.

|

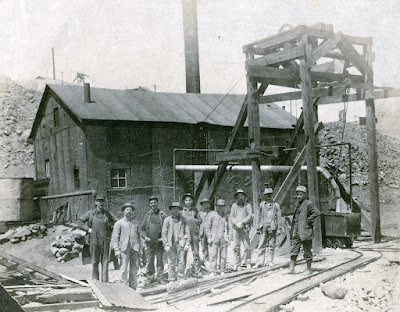

| Figure 5. View of the Requa Savage mine. Ten miners pose in front of the mine. Photographer and date unknown. Courtesy of the Cripple Creek District Museum. |

History records that, over time, Finegan was one of several prominent men associated with the Requa Savage mine. Records show that by 1912, the One Hundred and One Mining Company owned the mine (Mining Science, 1912). In 1913 The Mining Investor reported that Democratic Colorado State Senator Louis A. Van Tilborg (1870-1937) worked the Requa Savage mine for a short time. Van Tilborg, a druggist and an assayer, was the mayor of Cripple Creek from 1907 until 1911. He served in the Colorado legislature from 1911 to 1914. The presence of gas forced Van Tilborg to suspend work at the mine. Once the mine resolved the gas issues, production resumed under the lease of Kermit MacDermid, of the C.K. and N. Mining Company (The Mining Investor, 1913). By this time, the Requa Savage’s surface plant included a shaft house equipped with a steam hoist and electric compressor.

Although the Requa savage mine claimed a small area of land, it boasted five shafts. By 1914, the main shaft reached 700 feet deep (Consolidated Extension Mines Company, 1914). A crew of miners disappeared down the main shaft at the start of each shift and then drilled, blasted, and mucked in the shadows of the mine as they followed the occasional blossom of gold ore in barren rock. By 1914, the Requa Savage was owned by Rainbow Gold Mines Company. Rainbow Gold then leased it to another operator who, based on reports of good gold ore, planned to expand the development of the mine (Consolidated Extension Mines Company, 1914).

A new group of investors reincorporated the Requa Savage Gold Mining Company in November, 1915, as the Requa-Savage Mines Company with offices at 112 N. Tejon Street in Colorado Springs (Weed, 1918). A report showed the mine was producing ore in 1929 (Kiessling, 1929).

According to The Mining Journal (1935), Commonwealth Gold leased the Requa Savage mine. Mr. Wellington Symes, who was the president and general manager of the property, subleased it to a group in Denver; and Andy Vidgen, the mine superintendent, purchased new machinery to increase ore production (The Mining Journal, 1935).

As the years passed by, the ore decreased until the mine became unprofitable. The owners then closed the mine. Today, as you drive on Highway 67 between Cripple Creek and Victor, you will pass where the town of Arequa and the Requa Savage mine were once located. Both places now exist only in the pages of history. And we are reminded of Frank Finegan and how he emerged from obscurity and left his mark on time through his Civil War exploits and his ownership of a Cripple Creek mine.

Acknowledgments

I thank the Colorado Springs Oyster Club critique group for reviewing the manuscript, and Dr. Bob Carnein for his valuable comments and help in improving this paper.

References and further reading:

Colorado State Mining Directory, 1898: Denver, Western Mining Directory Company.

Consolidated Extension Mines Company, 1914, Referring to the Requa Savage mine on Beacon Hill in the Cripple Creek District, owned outright by Rainbow Gold Mines Company. United States Bureau of Mines: Colorado School of Mines Library Digital Collections, retrieved from https://mountainscholar.org/handle/11124/171813 on June 5, 2021.

Hoyer-Millar, C. C., 1896, The Cripple Creek Gold-Fields, Colorado, U.S.A: London, Eden Fisher & Co.

Kiessling, O.W., 1929, Mineral Resources of the US 1929: Washington DC, Dept of Commerce.

LeBoutillier, L., 2017, Secrets of the U.S. Civil War: North Mankato, MN, Capstone Press.

MacKell-Collins, J, 2014, Arequa Gulch: A Long Gone Town in Colorado, retrieved from https://janmackellcollins.wordpress.com/2014/03/20/arequa-gulch-a-long-gone-town-in-colorado/ on January 10, 2021.

McPherson, J., 2015, The War that Forged a Nation: Why the Civil War Still Matters: New York, Oxford University Press.

Mining Science, 1912, Denver, vol 65, no 1,682, April 18, 1912.

Portrait and Biographical Record of the State of Colorado, Part 2, 1899: Chicago, Chapman Publishing Company.

Stanchack, J., 2011, Eyewitness: Civil War: New York, DK Publishing.

The Mining Investor, 1913: Denver: The Mining Investor Publishing Co, no 1, vol 71, May 19, 1913.

The Mining Engineering Journal, 1910, New York, Hill Publishing Company, vol 89, Jan-June 1910.

The Mining Journal, 1935, February 28, 1935, pg. 18, retrieved from https://vredenburgh.org/mining_history/pdf/AMJ-1935.pdf on February 15, 2021.

Ward, G.C., 1990, The Civil War: An Illustrated History: New York, Alfred A. Knopf.

Weed, W. H., 1918, The Mines Handbook: New York, W. H. Weed Publishing.

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.